The original tomb for the society Wolf’s Head (founded in 1883) was built in a Dutch Ratskeller style by the venerable triumvirate of McKim, Meade, and White. “It even has a roof made of marble plates.” “The Book and Snake tomb, built in 1901, is supposed to be the most perfect reproduction of a Greek temple in the United States,” says Richards. The societies Book and Snake (founded in 1863) and Berzelius (founded in 1848) built their clubhouses as Greek temples. “The facade highly decorative and colorful stonework in yellow and purple.” An early design for the clubhouse shows that original intentions were for a structure much larger than what was ultimately built. “Hunt built in a Moorish revival, almost mosque-like style,” says Richards. Scroll and Key, founded in 1842, hired Gilded Age favorite Richard Morris Hunt-who had designed mansions like The Breakers, and Biltmore House for the Vanderbilt family-to design their tomb. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.Īs Bones became more established, other societies were looking to make more permanent holds around Yale. “That prohibition is still enforced today.” An architectural drawing from Richard Morris Hunt for the Scroll and Key tomb.

#Skull and bones tomb free

“The alumni put up the money for the tomb with a few conditions: First, they would be free to use the tomb, but they also required Bonesmen to never bring liquor inside,” adds Richards, who says that club life emphasizes learning about each other rather than drinking and revelry. As time went on, expansions were made to the side and back. When the Bones tomb originally opened, it was just a third of the size that it is today (when facing the tomb, the original bit is the leftmost portion of the facade). In his book, Richards pinpoints the exact Egyptian temples which inspired the clubhouse, like the Temple of Thebes at Kornou and the Temple of Karmac. “This was a statement to Yale that Skull and Bones was here to stay.” The practice of forming a corporation through alumni support and commissioning a clubhouse would be repeated by other Yale societies.īones hired architect Alexander Jackson Davis, who designed a clubhouse built out of brownstone in an Egyptian revival style: “All the buildings around the Bones tomb were Georgian brick,” says Richards. Alumni put up the money of the project, forming a corporation to buy land directly across the street from student dorms.

The first tomb at Yale was Skull and Bones, completed in 1856, about 25 years after the society was founded. While the Kenyon log cabin was built with function in mind, Richards expanded that when architects were tapped for Yale tombs, designs took on a more referential form, often echoing religious architecture.

#Skull and bones tomb windows

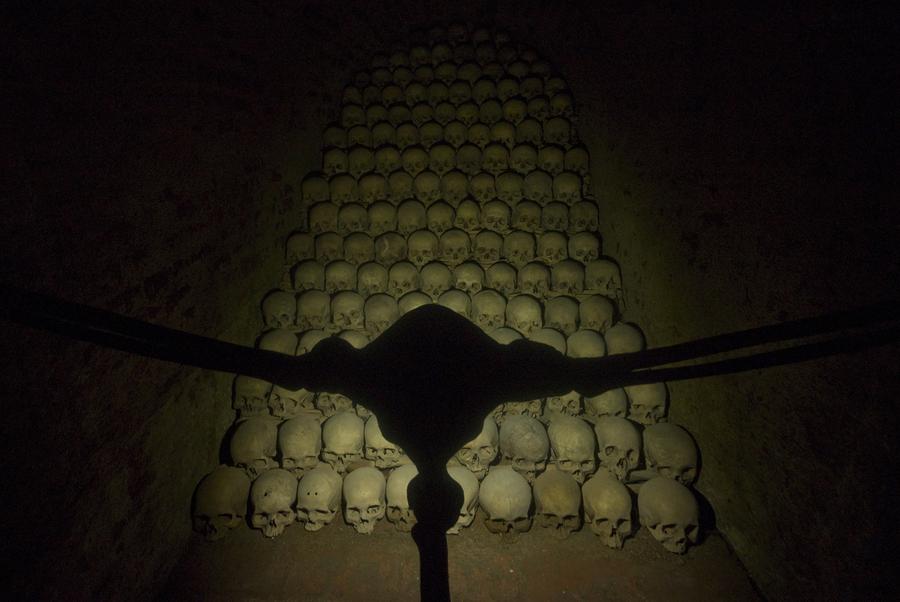

“There were air vents in the roof, but the whole concept of having sealed windows was the notion of privacy.” The Scroll and Key tomb. The first fraternity house was a log cabin with sealed windows at Kenyon College,” says David Alan Richards, author of Skull and Keys: The Hidden History of Yale’s Secret Societies -and a member of Skull and Bones himself. “Secret societies originated as what you and I know as fraternities. The name for these curious clubhouses? Tombs. And there’s no chance of a glimpse at what goes on inside, because they are also windowless. Clubhouse walls are so thick-made of sandstone and marble in some cases-that sound never escapes. But unlike normal clubhouses, members are rarely seen entering or leaving. Bush, and former Secretary of State John Kerry among its alumni.Īnd like any established club, many have their own clubhouse around New Haven.

Skull and Bones-arguably the most famous of Yale’s secret societies-alone counts President William Howard Taft, President George H.W.

But one thing we do know is that while each club is small-membership is often capped at 15 senior undergrads per society-the collective alumni represents some of the most powerful figures in the public realm. We don’t know much about the secret societies of Yale University. Welcome back to Period Dramas, a column that alternates between rounding up historic homes on the market and answering questions we’ve always had about older structures.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)